| Issue |

A&A

Volume 626, June 2019

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Article Number | A76 | |

| Number of page(s) | 14 | |

| Section | Galactic structure, stellar clusters and populations | |

| DOI | https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/201832869 | |

| Published online | 14 June 2019 | |

How the power spectrum of dust continuum images may hide the presence of a characteristic filament width

1

Laboratoire d’Astrophysique (AIM), CEA, CNRS, Université Paris-Saclay, Université Paris Diderot, Sorbonne Paris Cité, 91191 Gif-sur-Yvette, France

e-mail: [email protected], [email protected]

2

Laboratoire d’Astrophysique de Bordeaux, Univ. Bordeaux, CNRS, B18N, Allée G. Saint-Hilaire, 33615 Pessac, France

3

Department of Physics, Nagoya University, Furo-cho, Chikusa-ku, Nagoya, Aichi 464-8602, Japan

4

Institut d’Astrophysique Spatiale, CNRS, Univ. Paris-Sud, Université Paris-Saclay, Bâtiment 121, 91405 Orsay Cedex, France

5

I. Physik. Institut, University of Cologne, Zülpicher Str. 77, 50937 Koeln, Germany

6

INAF – Istituto di Astrofisica e Planetologia Spaziali, Via Fosso del Cavaliere 100, 00133 Roma, Italy

7

Instituto de Astrofísica e Ciências do Espaço, Universidade do Porto, CAUP, Rua das Estrelas, 4150-762 Porto, Portugal

8

University of Central Lancashire, Preston, Lancashire PR1 2HE, UK

Received:

21

February

2018

Accepted:

26

March

2019

Context. Herschel observations of interstellar clouds support a paradigm for star formation in which molecular filaments play a central role. One of the foundations of this paradigm is the finding, based on detailed studies of the transverse column density profiles observed with Herschel, that nearby molecular filaments share a common inner width of ∼0.1 pc. The existence of a characteristic filament width has been recently questioned, however, on the grounds that it seems inconsistent with the scale-free nature of the power spectrum of interstellar cloud images.

Aims. In an effort to clarify the origin of this apparent discrepancy, we examined the power spectra of the Herschel/SPIRE 250 μm images of the Polaris, Aquila, and Taurus–L1495 clouds in detail and performed a number of simple numerical experiments by injecting synthetic filaments in both the Herschel images and synthetic background images.

Methods. We constructed several populations of synthetic filaments of 0.1 pc width with realistic area filling factors (Afil) and distributions of column density contrasts (δc). After adding synthetic filaments to the original Herschel images, we recomputed the image power spectra and compared the results with the original, essentially scale-free power spectra. We used the χ2variance of the residuals between the best power-law fit and the output power spectrum in each simulation as a diagnostic of the presence (or absence) of a significant departure from a scale-free power spectrum.

Results. We find that χ2variance depends primarily on the combined parameter δ22 Afil. According to our numerical experiments, a significant departure from a scale-free behavior and thus the presence of a characteristic filament width become detectable in the power spectrum when δ22 Afil ⪆ 0.1 for synthetic filaments with Gaussian profiles and δ22 Afil ⪆ 0.4 for synthetic filaments with Plummer-like density profiles. Analysis of the real Herschel 250 μm data suggests that δ22 Afil is ∼0.01 in the case of the Polaris cloud and ∼0.016 in the Aquila cloud, significantly below the fiducial detection limit of δ22 Afil ∼ 0.1 in both cases. In both clouds, the observed filament contrasts and area filling factors are such that the filamentary structure contributes only ∼1/5 of the power in the image power spectrum at angular frequencies where an effect of the characteristic filament width is expected.

Conclusions. We conclude that the essentially scale-free power spectra of Herschel images remain consistent with the existence of a characteristic filament width ∼0.1 pc and do not invalidate the conclusions drawn from studies of the filament profiles.

Key words: local insterstellar matter / submillimeter: ISM / stars: low-mass / infrared: diffuse background

© ESO 2019

1. Introduction

Recent Herschel imaging observations of nearby molecular clouds, for example, those obtained as part of the Herschel Gould Belt Survey (HGBS; André et al. 2010), indicate that filamentary structures are characterized by a common inner width Wfil ∼ 0.1 pc, with only a factor of approximately two spread around this value, over a wide range of column densities (Arzoumanian et al. 2011, 2019; Koch & Rosolowsky 2015). If confirmed, the existence of such a characteristic filament width has remarkable implications for the star formation process and is one of the bases of a proposed filamentary paradigm for solar-type star formation (André et al. 2014). In particular, it may set a critical column density threshold above which most stars form in filamentary molecular clouds. For filaments of ∼0.1 pc width and a typical gas temperature of 10 K, the critical mass per unit length  M⊙ pc−1 (cf. Inutsuka & Miyama 1997) indeed translates to a critical column density Σgas, crit ∼ Mline, crit/Wfil ∼ 160 M⊙ pc−2, which is close to the background column density threshold above which prestellar cores are found with Herschel in nearby regions (e.g., Könyves et al. 2015; Marsh et al. 2016). Above this threshold, the star formation rate is observed to be directly proportional to the mass of dense molecular gas in both nearby clouds and external galaxies (e.g., Gao & Solomon 2004; Heiderman et al. 2010; Lada et al. 2010; Shimajiri et al. 2017).

M⊙ pc−1 (cf. Inutsuka & Miyama 1997) indeed translates to a critical column density Σgas, crit ∼ Mline, crit/Wfil ∼ 160 M⊙ pc−2, which is close to the background column density threshold above which prestellar cores are found with Herschel in nearby regions (e.g., Könyves et al. 2015; Marsh et al. 2016). Above this threshold, the star formation rate is observed to be directly proportional to the mass of dense molecular gas in both nearby clouds and external galaxies (e.g., Gao & Solomon 2004; Heiderman et al. 2010; Lada et al. 2010; Shimajiri et al. 2017).

Arzoumanian et al. (2011) suggested the existence of a characteristic filament width after fitting simple Gaussian or Plummer-like model profiles to the transverse profiles observed with Herschel for a broad sample of nearby filaments (see also Arzoumanian et al. 2019). In the analysis of Arzoumanian et al., thermally supercritical filaments (with  ) tend to have Plummer-like density profiles with a flat inner region of radius Rflat and a decreasing power-law wing ρ ∝ r−2 at larger radii. In contrast, low column density, thermally subcritical filaments (with

) tend to have Plummer-like density profiles with a flat inner region of radius Rflat and a decreasing power-law wing ρ ∝ r−2 at larger radii. In contrast, low column density, thermally subcritical filaments (with  ) tend to be better described by Gaussian density profiles.

) tend to be better described by Gaussian density profiles.

Why molecular filaments seem to share such a characteristic width is still a debated theoretical problem (e.g., Hennebelle & André 2013; Fischera & Martin 2012; Federrath 2016; Auddy et al. 2016). In order to ascertain whether the presence of this possibly universal filament scale is robust, the observational data also need to be investigated using various other means. In a recent paper, Panopoulou et al. (2017) tested the possibility of identifying a characteristic scale using a power spectrum analysis. In their study they argued that, had there been a characteristic filament width, its signature should have manifested itself in the power spectrum of Herschel images of nearby clouds, either as a kink or as a change in slope at an angular frequency corresponding to the characteristic scale.

In the present paper, we revisit the latter issue from an observer’s standpoint, exploring the parameter space with realistic filament properties consistent with the observational data, in particular taking into account realistic distributions of filament contrasts and area filling factors. To this end, we selected two extreme regions imaged by the HGBS, namely the Polaris translucent cloud, mainly dominated by low density subcritical (Mline < Mline, crit) filaments, and the Aquila complex, which contains a fair population of high column density supercritical (Mline > Mline, crit) filaments. We also used the B211/B213 field in the Taurus cloud, which is dominated by a single, marginally supercritical filament.

The layout of the paper is as follows. In Sect. 2 we describe the construction of synthetic filament images and their power spectra. In Sect. 3, we develop a diagnostic for the detection of a characteristic filament width in a power spectrum plot. We also develop a diagnostic for the detection of a characteristic filament width in a power spectrum plot. In Sects. 4 and 5, we perform a power spectrum analysis of the Herschel images of the Polaris and Aquila clouds, respectively, and compare the results to those obtained on synthetic maps after adding simulated filaments. In Sect. 6, we compared power spectra of a subregion of Taurus molecular cloud encompassing the Taurus main filament to a synthetic filament with similar physical properties as B211/B213. In Sect. 7, we investigate the combined effect of filament column density contrast (δc) and area filling factor (Afil). Finally, we summarize our results in Sect. 8.

2. Construction of synthetic filaments and their power spectra

Figure 1 shows an example of a synthetic filament with a transverse Gaussian profile and a projected spatial inner width (FWHM) of 0.1 pc at a distance of 140 pc. Mathematically, the 2D image of a filament with a Gaussian profile can be expressed as

|

Fig. 1. Image of a simulated filament with a Gaussian transverse profile and a FWHM width of 0.1 pc, projected at a distance of 140 pc. Here, the level of filament contrast was adjusted so that δc ∼ 10. |

where, C is the amplitude factor (related to the filament contrast) of the delta line function δL(ax + by + c), ΠL is a rectangle function, and the ⋆ symbol denotes the convolution operator. The delta line function assumes a value of unity when its parameter ax + by + c = 0, and zero elsewhere. The expression ax + by + c = 0 is the equation of a straight line where the a, b coefficients determine the slope of the straight line and c is the intercept. The rectangle function, ΠL, which has a value of unity over the length L of the line function and zero elsewhere, transforms the line into a line-segment of length L. In order to make a Gaussian filament profile, we convolve the entire line segment [δ(ax + by + c)×ΠL] with a Gaussian kernel, Gθfil(x, y), of full width at half maximum FWHM = θfil.

The FWHM of the Gaussian kernel =θfil is chosen such that the projected spatial width is Wfil. To create a characteristic Wfil inner width of a filament at a distance d, the required θfil is

The choice of the parameter C depends upon the required level of filament contrast defined as δc = (Ipeak − Ibkg)/Ibkg and on the dilution factor of the convolution kernel,

For example, in order to create a Gaussian filament profile of spatial FWHM = 0.1 pc and contrast δc = 0.4 at the distance of Polaris (d = 140 pc, Falgarone et al. 1998), we used a Gaussian convolution kernel of θfil ∼ 147″ (see Eq. (3)), and a contrast amplitude of C ∼ 0.4 × 147″/θpix, where θpix is the pixel size of the image. We adopted a pixel size θpix = 6″ for Herschel/SPIRE 250 μm images (18.2″ beam resolution).

The Fourier transform of a 2D image can be expressed as

where dx dy is the infinitesimal surface area, and ∫dx dy = S is the total surface area, S, covered by the map. For an image of a single cylindrical filament, most of the contribution to the integral in Eq. (4) comes from integration over the central part of the filament which encloses 75% of the total intensity fluctuations.

The power spectrum of a cylindrical intensity distribution can be written analytically as

where  is the Fourier transform of the delta line function δL(ax + by + c) and

is the Fourier transform of the delta line function δL(ax + by + c) and  is the Fourier transform of the convolution kernel. The power spectrum of the Gaussian kernel,

is the Fourier transform of the convolution kernel. The power spectrum of the Gaussian kernel,  , is also a Gaussian, and its FWHM width Γfil is related to the FWHM width θfil of Gθfil(x, y) through the relation:

, is also a Gaussian, and its FWHM width Γfil is related to the FWHM width θfil of Gθfil(x, y) through the relation:

One may thus expect a characteristic filament width θfil to lead to a signature in the power spectrum at angular frequencies kfil ∼ Γfil.

For multiple, randomly distributed filaments, as in the simulations discussed below, it is not possible to obtain the power spectrum analytically. We therefore used the IDL-based routine FFT to compute the power spectrum. Nevertheless, Eq. (5) is useful to appreciate how the power spectrum of an image with a single filament is dominated by the power spectrum of the convolution kernel. As an illustration, Fig. 2b displays the power spectra of images including a single model filament with either a Gaussian or a Plummer-like density profile. The red curve in Fig. 2a shows the radial profile of the Gaussian filament displayed in Fig. 1. The over-plotted black curves show the profiles of filaments featuring Plummer-like power-law wings at large radii, with power-law slopes ranging from p = 1.5 to p = 4. The flat inner region of each Plummer-like model filament had a constant Rflat of ∼0.03 pc. An example of filament with a transverse Plummer profile is shown in Fig. A.1. Figure 2b displays the power spectra corresponding to the filament profiles shown in Fig. 2a. At high angular frequencies, the power decreases exponentially following the same trend as the power spectrum of the convolution kernel. An example of a filament with a Plummer-like radial profile is shown in Fig. A.1.

|

Fig. 2. Transverse profiles of several simple model filaments (a) and corresponding power spectra (b). Panel a: red curve shows the Gaussian column density profile of the filament displayed in Fig. 1, which has a FWHM width of 0.1 pc at a distance of 140 pc. The red vertical line marks the FWHM of the Gaussian profile. The black dashed and dotted curves display Plummer-like filament profiles with Rflat ∼ 0.03 pc and logarithmic slopes p = 1.5, 2, 2.6, and 4. Panel b: all power spectra were normalized to 1 at the lowest angular frequency |

3. Diagnosing the presence of a characteristic filament width from image power spectra

In general, dust continuum images of the diffuse, cold interstellar medium (ISM) are well described by power-law power spectra, often attributed to the turbulent nature of the flow. Herschel images are also revealing a wealth of filaments. In the following we assume that these two contributions to the emission can be treated separately, in real space

Under the assumption that the filaments are randomly oriented and are not correlated with the diffuse background, we can express the total power spectrum as:

where PISM(k) is the total power spectrum of the ISM, and Pbkg(k) and Pfil(k) represent the power spectra of the diffuse background and filament population, respectively. It is fair to assume that the power spectrum of dust images of the diffuse ISM follows a power-law, Pbkg(k) ∝ kγ with γ ∼ −2.7. From Fig. 2 and Eqs. (5) and (6), it is clear that the contribution of a population of filaments with constant width θfil to the total power spectrum is not confined to a narrow range of spatial frequencies, but rather follows a shallow power law at angular frequencies lower than Γfil.

In order to better visualize the filament contribution, we fit a power-law to the total power spectrum, PISM(k), and then inspect the residuals,

as a function of angular frequency. To quantify the magnitude of the deviation from the best power-law fit, we use the  as our metric. We calculate the variance of the residuals in the vicinity of kfil where the contribution of filament power is expected to be maximum1. We define the variance as

as our metric. We calculate the variance of the residuals in the vicinity of kfil where the contribution of filament power is expected to be maximum1. We define the variance as

where Res(k) is the residual at angular frequency k defined by Eq. (9), and Nfreq is the total number of frequency modes2 between kmin and 1.5 × kfil. The upper bound in the above summation is set to 1.5 × kfil in a conservative sense, since the power spectrum of constant-width filaments drops at k > kfil (see Fig. 2b), and Res(k) is therefore dominated by the diffuse ISM contribution for k > kfil. In principle, the image power spectrum of a scale-free ISM will have residuals close to zero, and any significant deviation of the residuals from zero at k < kfil will be primarily due to the power spectrum of filaments (see Eq. (8)). Thus, one expects ![$ \chi^2_{\rm variance} \propto \sum \left[P_{\rm best~fit}(k) - P_{\rm ISM}(k)\right]^2 \propto \sum P_{\rm fil}(k)^2 $](/articles/aa/full_html/2019/06/aa32869-18/aa32869-18-eq26.gif) . Simple dimensional analysis of the Parseval relation between Pfil(k)2 and |Ifil(x, y)|2 provides deeper insight into the connection between

. Simple dimensional analysis of the Parseval relation between Pfil(k)2 and |Ifil(x, y)|2 provides deeper insight into the connection between  and observable parameters of the filament population:

and observable parameters of the filament population:

where [x] in square brackets denotes the dimension of quantity x. Dimensional analysis thus suggests that  must be a function of

must be a function of  Afil:

Afil:

The  dependence comes from exploiting Eqs. (1) and (3), while the area filling factor Afil ≡ Sfil/S dependence comes from the fact that only the effective area Sfil over which filaments are distributed contribute to the integral on the right-hand side of Eq. (11). For low Afil and δc the variance is very small, while for high Afil and/or high δc the variance metric can be very high. We will explore the

dependence comes from exploiting Eqs. (1) and (3), while the area filling factor Afil ≡ Sfil/S dependence comes from the fact that only the effective area Sfil over which filaments are distributed contribute to the integral on the right-hand side of Eq. (11). For low Afil and δc the variance is very small, while for high Afil and/or high δc the variance metric can be very high. We will explore the  parameter space in more detail in Sect. 7 below.

parameter space in more detail in Sect. 7 below.

The magnitude/amplitude of excess power in the ISM power spectrum PISM(k) relative to the best-fit power law model power spectrum at a characteristic frequency kfil depends upon the combined effect of the mean filament contrast in the image and the fractional area covered by the filaments, Afil. The area filling factor Afil can be expressed as  , where Li is the length of the ith filament, Wfil the transverse filament width (∼0.1 pc), S the total area coverage of the image being analyzed, and Nfil the total number of filaments in the image.

, where Li is the length of the ith filament, Wfil the transverse filament width (∼0.1 pc), S the total area coverage of the image being analyzed, and Nfil the total number of filaments in the image.

4. Power spectrum of the Polaris Herschel data

In this section, we analyze the Herschel/SPIRE image of the Polaris Flare cloud at 250 μm (Miville-Deschênes et al. 2010; Ward-Thompson et al. 2010; see also Schneider et al. 2013), which covers an area of 3.0° × 3.3° and is shown in Fig. 3a) at the native (diffraction-limited) beam resolution of 18 2. For our analysis, a pixel size of 6″ was adopted3.

2. For our analysis, a pixel size of 6″ was adopted3.

|

Fig. 3. Panel a: Herschel/SPIRE 250 μm emission image of a part of the Polaris cloud. The HPBW angular resolution is 18 |

The Polaris Flare image displays a spectacular distribution of low column density filaments. All of these filaments are thermally subcritical. The mean peak surface brightness contrast of these filaments over the local background is around ⟨δc⟩∼0.9, but the filaments occupy only a small fraction ∼2% of the total surface area, leading to  Afil ∼ 0.016.

Afil ∼ 0.016.

To first order, the transverse structure of the Polaris filaments is well described by Gaussian profiles with a FWHM of ∼0.1 pc (assuming a distance ∼140 pc for the Polaris cloud) (Arzoumanian et al. 2011, 2019). Miville-Deschênes et al. (2010) carried out a power spectrum analysis for the Polaris image over spatial scales ranging from 0.01 pc to 10 pc. The power spectrum revealed a continuous power-law, P(k)∝kγ, with an exponent of γ = −2.65 down to the scale of the beam, suggesting a scale-free image. Following the same scheme as Miville-Deschênes et al. (2010), we derived the power spectrum of a sub-field4 of Polaris shown in Fig. 3. Prior to computing of power spectrum, we apodized the edges of the image by a sine function to ensure smooth periodic boundary condition. After subtracting the noise power spectrum level estimated from the mean power at angular frequencies k > 3.5 arcmin−1, we corrected for convolution effects by dividing the observed power spectrum by the power spectrum of the Herschel telescope beam at 250 μm (Martin et al. 2010) obtained from scans of Neptune. In order to derive the power spectrum slope, we then fitted a power-law model of the form Psky(k) = AISMkγ + P0 to the corrected power spectrum over the range of angular frequencies 0.025 arcmin−1 < k < 2 arcmin−1, as described in Miville-Deschênes et al. (2010). In Fig. 3b, we show the power spectrum of the Polaris image over the range of angular frequencies used in the power-law fit. The red curve represents the best-fit power law with γ = −2.63 ± 0.1, which is very close to the γ = −2.65 ± 0.1 value obtained by Miville-Deschênes et al. (2010). Visual inspection shows that there is no clear spectral signature of a characteristic scale embedded in the observed power spectrum. Figure 3c shows the residuals [PBest − fit(k) − PPolaris(k)]/PPolaris(k) as a function of angular frequency. Any significant kink or distortion in the power spectrum due to the presence of a characteristic scale should in principle be captured as a significant deviation from zero in the plot of residuals. The plot of residuals for the Polaris Flare image (Fig. 3c) does not exhibit such a deviation.

In order to critically analyze this finding, we performed a suite of numerical experiments by injecting synthetic filaments separately into 1) the original Herschel/SPIRE 250 μm image of Polaris, and 2) the filament-subtracted image obtained after applying the getfilaments algorithm (Men’shchikov 2013) to the Herschel/SPIRE image to remove most of the real filamentary structures. We repeated the same power spectrum analysis as described above on both sets of modified Herschel images (see Sects. 4.2 and 4.3 below). For this analysis, we preferred to use SPIRE 250 μm data rather than 18 2 column density images produced from the combination of Herschel data at 160 μm to 500 μm (cf. Palmeirim et al. 2013) because the former are less affected by noise and better behaved from a power-spectrum point of view (cf. Miville-Deschênes et al. 2010).

2 column density images produced from the combination of Herschel data at 160 μm to 500 μm (cf. Palmeirim et al. 2013) because the former are less affected by noise and better behaved from a power-spectrum point of view (cf. Miville-Deschênes et al. 2010).

4.1. Construction of an image with synthetic filaments

To create a synthetic filament image, the first step was to generate a map of randomly oriented 1D delta line functions as described in Sect. 2. Then, we convolved this initial synthetic map with a Gaussian kernel such that the projected spatial FWHM width of the kernel was 0.1 pc as described in Sect. 2. When creating synthetic filaments we neglected the fluctuations observed along real Herschel filaments (Roy et al. 2015), because the contrast of these fluctuations above the average filament is ≪1, and also the area filling factor of these fluctuations is very small. To maximize the effect of a characteristic width in our simulations, we fixed the FWHM width of the Gaussian filaments to a strictly constant value. We controlled the contrast parameter C of each filament by measuring the local background emission in the close vicinity of the filament within the background image. The distribution of the contrast parameter was chosen to reflect the observed distribution in each region. In the simulation, we varied the angular length of the filaments randomly between a minimum of 30 × 18 2 = 546″ and a maximum of 70 × 18

2 = 546″ and a maximum of 70 × 18 2 = 1274″, corresponding to 0.4 to 0.9 pc at d = 140 pc. Figure 4a shows one such realization including a population of synthetic filaments with a lognormal distribution of contrasts in the range 0.3 < δc < 2.0, co-added to the original map of Polaris. In this example, the population of synthetic filaments has an area filling factor Afil ∼ 3.2%.

2 = 1274″, corresponding to 0.4 to 0.9 pc at d = 140 pc. Figure 4a shows one such realization including a population of synthetic filaments with a lognormal distribution of contrasts in the range 0.3 < δc < 2.0, co-added to the original map of Polaris. In this example, the population of synthetic filaments has an area filling factor Afil ∼ 3.2%.

|

Fig. 4. Same as Fig. 3 but for a 250 μm image with an additional population of synthetic filaments. The population of synthetic filaments has a lognormal distribution of contrasts in the range 0.3 < δc < 2.0 with a broad peak around δpeak ∼ 0.9. The overall area filling factor of the synthetic filaments is Afil ∼ 3% and the |

4.2. Effect of synthetic filaments on the power spectrum of the Polaris image

Next, we investigated the effect of synthetic filaments on the power spectrum of the Polaris original image on one hand, and the power spectrum of the filament-subtracted Polaris image on the other hand. First, we discuss the case of the Polaris original image.

Figure 4b shows the total power spectrum of the Polaris image in Fig. 4a, which includes a population of synthetic filaments with a log-normal distribution of contrasts, δc. In Fig. 4, the range of contrast values in the synthetic distribution varied in the range 0.3 < δc < 2.0 with a peak at δpeak ∼ 0.9. The weighted average of the contrast over the length of the simulated filaments is ⟨δc⟩∼0.85. In Fig. 4a, the synthetic filaments are clearly visible against their local background. The best power-law fit to the power spectrum (red curve) has a logarithmic slope γ = −2.7 ± 0.1, slightly steeper than the slope of the Polaris original image. The vertical dashed line marks the angular frequency, kfil = Γ ∼ (0.6/θfil)∼0.24 arcmin−1, corresponding to the characteristic angular width of the synthetic filaments, θfil = 147″ (i.e., 0.1 pc at d = 140 pc). Comparison of Figs. 4b and 3b shows that the synthetic filaments contribute an insignificant amount of power around kfil = 0.24 arcmin−1, which can hardly be detected without prior knowledge of the power spectrum of the original ISM image. Figure 4c plots the normalized residuals between the best power-law fit and the power spectrum data, [PBest − fit(k)−PPolaris(k)]/PPolaris(k), as a function of angular frequency. These residuals (red filled circles) can be compared with the residuals obtained with the original image, represented by black triangles in both Figs. 3c and 4c. Again, no clear signature of the presence of synthetic filaments can be detected despite the fact that they have a characteristic width.

Now let us investigate the power spectrum of each component more closely to understand the absence of any detectable signature in the total power spectrum. The blue curve and the green dashed curve in Fig. 4b show the power spectrum of the synthetic filament image and that of the original image, respectively. Note that the power spectrum of the filament image, Pfil(k), is lower than the power spectrum PPolaris(k) at k = kfil by a factor of ∼5. This is because the population of synthetic filaments only have moderate area filling factor (Afil ∼ 3.2%) and contrast (⟨δc⟩∼0.85). In this experiment, the product of the area filling factor with the square of the column density contrast ( ) was in agreement with the real filaments observed in Polaris (which have Afil ⟨δc⟩2 ∼ 0.01 – cf. Arzoumanian et al. 2019). The additional power introduced by the synthetic filaments is not localized in the vicinity of kfil but rather spread out at angular frequencies k ≲ kfil, following a shallow power-law, whereas the power at high angular frequencies at k > kfil drops sharply. Given the choice of δc and Afil made here, the relative contribution of filaments to the total power spectrum, Pfil(k)/PPolaris(k) is highest in the vicinity of kfil, but too small to create any detectable feature in the power spectrum.

) was in agreement with the real filaments observed in Polaris (which have Afil ⟨δc⟩2 ∼ 0.01 – cf. Arzoumanian et al. 2019). The additional power introduced by the synthetic filaments is not localized in the vicinity of kfil but rather spread out at angular frequencies k ≲ kfil, following a shallow power-law, whereas the power at high angular frequencies at k > kfil drops sharply. Given the choice of δc and Afil made here, the relative contribution of filaments to the total power spectrum, Pfil(k)/PPolaris(k) is highest in the vicinity of kfil, but too small to create any detectable feature in the power spectrum.

When the contrast and/or filling factor of the synthetic filaments is gradually increased, the spectral imprint in the resulting power spectrum becomes more and more pronounced. Figure B.2a shows a simulated image including a population of synthetic 0.1 pc filaments with contrast δc ∼ 1.1 and area filling factor Afil ∼ 7.2%. This is quite an extreme scenario for a non-star-forming molecular cloud with low column density such as Polaris. Figure B.2b shows the corresponding power spectra, which should be compared to those in Fig. 4b. It can be seen that the amplitude of the synthetic power spectrum in Appendix B (with contrast ⟨δc⟩∼1.1 and Afil ∼ 7.2%) is higher by a factor of 3 to 4 than the amplitude of the power spectrum of Fig. 4b (with contrast ⟨δc⟩∼0.85 and Afil ∼ 3.2%), mostly due to the increase in the combination of contrast parameter and area-filling factor ⟨δc⟩2 Afil between the two simulations [∼(1.1/0.85)2 × (7.2/3.2)( ∼ 3.7)]. The red curve in Fig. B.2b shows the best power-law fit which has a logarithmic slope γ = −2.96 ± 0.1. At k ≲ kfil, there is a significant enhancement of power due to the fact the synthetic filament power spectrum Pfil(k) is now comparable to the Polaris power spectrum PPolaris(k) at k ≲ kfil. Accordingly, in this case, the residuals between the best power-law fit and the total power spectrum data depart significantly from zero at k ≲ kfil (cf. Fig. B.2c). It is to be borne in mind, however, that the population of synthetic filaments used in Appendix B have much higher contrast and area filling factor than the actual filaments of the Polaris cloud (compare Figs. B.2a and 3a).

4.3. Effect of synthetic filaments on the power spectrum of the filament-subtracted image

So far we have explored the response of the power spectrum to a synthetic population of filaments injected into the original Herschel image, which itself includes emission from real filamentary structures. It is instructive to assess the extent to which the real filaments present in the image may reduce the relative contribution of synthetic filaments. In order to evaluate this we adopted two approaches – first, we subtracted the emission of at least the most prominent real filamentary structures from the Polaris 250 μm image using the getfilaments algorithm (Men’shchikov 2013, see Fig. B.1b for the resulting filament-subtracted image) and then repeated the same experiment as described in Sect. 4.1. Second, we examined the effect of filaments embedded in a typical scale-free synthetic cirrus images (see Appendix C). In order to be consistent, we used the same population of synthetic filaments as in Sects. 4.1 and 4.2.

Figure 5 summarizes the effect of the synthetic 0.1 pc filaments on a background image which is essentially devoid of real filamentary structures. Although the logarithmic power-spectrum slope of the background image is shallower (γbkg = −2.5) than that of the Polaris original image (γobs = −2.7), the overall morphology remains the same. In particular, the power spectrum of the synthetic filament component is still significantly lower than the total power spectrum of the background image, even though the power arising from real filaments has been subtracted from that image. The  of the filament-subtracted background image is 0.04, very close the

of the filament-subtracted background image is 0.04, very close the  value obtained for the Polaris original image. Moreover, there is still no clear signature of the presence of synthetic filaments in the residuals plot (Fig. 5c). Similar conclusions were reached in Appendix C in the case of synthetic filaments added to a purely synthetic background image.

value obtained for the Polaris original image. Moreover, there is still no clear signature of the presence of synthetic filaments in the residuals plot (Fig. 5c). Similar conclusions were reached in Appendix C in the case of synthetic filaments added to a purely synthetic background image.

|

Fig. 5. Same as Fig. 4 for synthetic filaments added to a filament-subtracted image of Polaris obtained with getfilaments (Men’shchikov 2013). The population of synthetic filaments is the same as that in Fig. 4. Panel b: green dashed line shows the best power-law fit to the power spectrum of the filament-subtracted background image of Polaris (with no synthetic filaments), which has a slope of γ = −2.4 ± 0.1. The solid black curve shows the total power spectrum of the filament-subtracted image plus synthetic filaments. The best-fit power-law (red curve) has a slope of γ = −2.5 ± 0.1, slightly steeper than the slope of the power spectrum of the filament-subtracted background image (dashed green curve). The blue curve is the power spectrum of the image containing only synthetic filaments. Panel c: black triangles are the same as in Fig. 3c and the red dots show the residuals between the best-fit power-law model and the power spectrum of the image including synthetic filaments. The |

5. Exploring the parameter space with simulations in the Aquila cloud

The Aquila molecular cloud harbors a statistically significant number of filaments with a wide range of filament column density contrasts (Könyves et al. 2015; Arzoumanian et al. 2019), allowing us to derive a realistic distribution of contrasts which can then be used for constructing more realistic populations of synthetic filaments.

5.1. Observed filament properties in Aquila

In contrast to the Polaris cloud, the Aquila molecular cloud is an active star forming complex at a distance5 of 260 pc, including several supercritical filaments (André et al. 2010; Könyves et al. 2015). Figure 6a shows the Herschel/SPIRE 250 μm image of the Aquila cloud, which covers a projected sky area of 3.4° × 3.2°. The corresponding power spectrum is shown in Fig. 6b.

|

Fig. 6. Panel a: Herschel/SPIRE 250 μm image of the Aquila cloud at the native resolution of 18 |

As part of a systematic analysis of filament properties in nearby clouds based on HGBS data, Arzoumanian et al. (2019) took a census of filamentary structures in Aquila. They obtained a distribution of filament column density contrasts which can be conveniently approximated by the two-segment power law shown in Fig. 7: dN/dlog(δc) ∼ const for 0.3 ≤ δc ≤ 1, and dN/dlog(δc) ∼  for 1 ≤ δc ≤ 4. This observed distribution of filaments contrasts has a peak around

for 1 ≤ δc ≤ 4. This observed distribution of filaments contrasts has a peak around  and spans a broad range from low δc ∼ 0.3 values to fairly high δc ∼ 4 values. The weighted average column density contrast of the filaments observed in Aquila is ⟨δc⟩∼1, and their area filling factor is Afil ∼ 3%. While the census of filaments obtained by Arzoumanian et al. (2019) may be affected by incompleteness issues for low-contrast6 (δc ≪ 1) filaments, it should be essentially complete for high-contrast (δc ≳ 1) supercritical filaments.

and spans a broad range from low δc ∼ 0.3 values to fairly high δc ∼ 4 values. The weighted average column density contrast of the filaments observed in Aquila is ⟨δc⟩∼1, and their area filling factor is Afil ∼ 3%. While the census of filaments obtained by Arzoumanian et al. (2019) may be affected by incompleteness issues for low-contrast6 (δc ≪ 1) filaments, it should be essentially complete for high-contrast (δc ≳ 1) supercritical filaments.

|

Fig. 7. Two-segment power-law approximation (black solid lines) to the distribution of filament column density contrasts observed in the Aquila molecular cloud (Arzoumanian et al. 2019): dN/dlog(δc)∼const for 0.3 ≤ δc ≤ 1, and d |

5.2. Effect of a synthetic population of filaments on the power spectrum

Using a methodology similar to that employed in Sect. 4 for Polaris, we added a population of synthetic filaments with fixed 0.1 pc width to a filament-subtracted Herschel image of the Aquila region at 250 μm. The distribution of column density contrasts7 for the synthetic filaments was constructed to be consistent with observations and is represented by the histogram in Fig. 7. The weighted mean contrast of the whole population of synthetic filaments was ⟨δc⟩∼0.96. Like in the Polaris case, the background image was obtained from the Herschel/SPIRE 250 μm of the Aquila cloud image after removing observed filaments using the getfilaments algorithm (Men’shchikov 2013). The resulting synthetic image is shown in Fig. 8a. Figure 8b shows the power spectrum of each component in the synthetic image: the blue curve corresponds to the contribution of the synthetic filament distribution, while the black curve is the total power spectrum of the Aquila background plus filament image.

|

Fig. 8. Same as Fig. 6 but for a simulated image including a population of synthetic filaments with a realistic distribution of column density contrasts (see Fig. 7) added to a filament-subtracted image of the Aquila cloud. Panel a: simulated image. The weighted average contrast ⟨δc⟩ of the distribution of synthetic filaments is 0.96 and the total area covering factor Afil is 5.5%, leading to |

It can be seen in Fig. 8b that the amplitude of the power spectrum arising from the population of synthetic filaments (blue curve) is lower than the amplitude of the power spectrum of the Aquila original image (green dashed curve) by a factor of ∼5 at k ∼ kfil ∼ (0.6/θfil)∼0.45 arcmin−1, corresponding to the characteristic angular width of the synthetic filaments, θfil = 79″ (i.e., 0.1 pc at d = 260 pc). Clearly, the power contribution of the synthetic filaments is not strong enough to be detected in the power spectrum. The residuals of the best power-law fit with respect to the power spectrum of the Aquila original image are shown as black triangles in Fig. 8c as a function of angular frequency. The red solid circles in Fig. 8c represent similar residuals for the Aquila background plus synthetic filament image. Based on this simulation, we conclude that the injection of a population of synthetic filaments with a distribution of column density contrasts similar to that observed in the real Aquila image does not have any significant effect on the shape of the power spectrum.

In Appendix B, we also explore a more extreme case where the distribution of column density contrasts for the injected synthetic filaments is similar in shape to the distribution shown in Fig. 7, but with higher mean contrast  and maximum contrast

and maximum contrast  . In this extreme case, the population of synthetic filaments is strong enough to produce a detectable signature in the resulting power spectrum.

. In this extreme case, the population of synthetic filaments is strong enough to produce a detectable signature in the resulting power spectrum.

6. Power spectrum of synthetic data with a single, prominent filament

We also examined the power spectrum of an image with a single dominant filament such as the Herschel/SPIRE 250 μm image of the B211/B213 region in the Taurus cloud at d ∼ 140 pc (Fig. 9a)8. For the present purpose, we only used a 1.2° × 1.0° portion of the original SPIRE image of B211/B213, where a single filament dominates over a length scale of > 1.5° (or > 4 pc). Palmeirim et al. (2013) studied the column density structure of the B211/B213 filament in detail and found that it is accurately described by a Plummer-like cylindrical density distribution with flat inner radius Rflat ∼ 0.035 pc and power-law index p = 2 ± 0.2 at larger radii up to an outer radius Rout ∼ 0.4 pc. Moreover, Palmeirim et al. (2013) suggested that the Taurus main filament accretes mass from the ambient cloud through a network of lower-density striations, observed roughly perpendicular to the main filament. Based on these findings, we constructed a synthetic image of a Plummer-like filament of length ∼4 pc, with the same Plummer parameters as quoted above, and positioned horizontally in a ∼1.5° × 1.5° two-dimensional box. The contrast of the synthetic filament was chosen to be δc ∼ 6, a value close to the observed contrast of the B211/B213 filament in the SPIRE 250 μm image (see Palmeirim et al. 2013). To mimic the observations, we added a population of synthetic cores with Bonnor-Ebert-like radial profiles randomly distributed along the filament. The flat inner radius Rflat of the cores was fixed to a constant value of 0.02 pc. In order to create a synthetic background image similar to the real data, we carefully studied the statistical properties of the Herschel 250 μm image in the vicinity of the Taurus main filament. We selected a rectangular field to the north of the B211/B213 main filament such that the nearest edge of the field was at least 0.2 pc away from the filament crest. We then evaluated the power spectrum of this field and found a logarithmic slope γ ∼ −3.0 ± 0.2. A purely synthetic background image was next generated using a non-Gaussian fractional Brownian motion (fBm) technique (Miville-Deschênes et al. 2003) with positive values and statistics such that the power spectrum of the background field had a logarithmic slope similar to that of the Taurus background field (γback = −3.0). To make the synthetic background image more similar to the Taurus observations, we also inserted a distribution of lognormally distributed low-contrast (0.1 < δc < 0.5) filamentary structures with Gaussian profiles perpendicular to the main filament as a proxy for the observed striations. We placed perpendicular striations at a regular separation of ∼0.1 pc to match the observations of Tritsis & Tassis (2018). The width of these synthetic striations was fixed to 0.08 pc.

|

Fig. 9. Left panel: Herschel/SPIRE 250 μm image of the B211/B213 region in Taurus at the native beam resolution of 18.2″, but rotated in equatorial coordinates in clockwise direction by 37.4°. (see Palmeirim et al. 2013). Right panel: fully synthetic image mimicking the main features of the real image shown in the left panel, and resulting from the co-addition of a synthetic filament image and a synthetic background image. The synthetic filament image was based on the Plummer-like model of the B211 filament reported by Palmeirim et al. (2013): flat inner radius Rflat = 0.035 pc, contrast δc ∼ 6, and power-law index p = 2 at large radii. The background image was modeled as non-Gaussian cirrus fluctuations with a logarithmic power spectrum slope of −3 (see text for details), plus low-contrast filamentary structures resembling striations. The synthetic striations were placed such that their long axis is perpendicular to the main filament at a regular separation of 0.1 pc. |

The final image, obtained after co-adding all three synthetic image components (background, striations, and main filament with embedded cores), is shown in Fig. 9b. For reference and comparison with the synthetic data discussed in Sects. 4 and 5, this image has  Afil ∼ 0.125. Figure 10 compares the power spectrum of the synthetic image (red curve) with that of the Herschel/SPIRE 250 μm image (black solid curve). The vertical dashed line in Fig. 10 marks the angular frequency kfil corresponding to a linear scale of ∼0.1 pc, i.e., roughly the inner width of both the synthetic filament and the B211/B213 filament. Clearly, like for the other two regions considered in this paper, the power spectrum of the Taurus B211/B213 data does not reveal any “kink” or “break” at frequencies close to kfil. Furthermore, this is also the case for the synthetic data of Fig. 9b, despite the presence of a prominent cylindrical filament with ∼0.1 pc inner diameter. This further illustrates how the characteristic scale of embedded structures may be hidden and undetectable in a global power spectrum.

Afil ∼ 0.125. Figure 10 compares the power spectrum of the synthetic image (red curve) with that of the Herschel/SPIRE 250 μm image (black solid curve). The vertical dashed line in Fig. 10 marks the angular frequency kfil corresponding to a linear scale of ∼0.1 pc, i.e., roughly the inner width of both the synthetic filament and the B211/B213 filament. Clearly, like for the other two regions considered in this paper, the power spectrum of the Taurus B211/B213 data does not reveal any “kink” or “break” at frequencies close to kfil. Furthermore, this is also the case for the synthetic data of Fig. 9b, despite the presence of a prominent cylindrical filament with ∼0.1 pc inner diameter. This further illustrates how the characteristic scale of embedded structures may be hidden and undetectable in a global power spectrum.

|

Fig. 10. Comparison of the power spectrum of the Herschel/SPIRE 250 μm image of Fig. 9a (black solid curve) with that of the synthetic image of Fig. 9b (red curve). Note the absence of any significant feature around k ∼ kfil (vertical dashed line) in both power spectra. |

7. Combined effect of filament contrast and area filling factor

In order to further explore the dependence of the total power spectrum on filament contrast and area filling factor, we performed two separate grids of 20 × 20 Monte-Carlo simulations based on two different sets of synthetic filament populations, one with Gaussian radial profiles and the other with Plummer-like profiles with p = 2 (see Appendix A). The simulated images spanned a broad range of average filament contrasts ⟨δc⟩ and filling factors Afil. In practice, we injected a fixed number of synthetic filaments of 0.1 pc width in the Herschel/SPIRE 250 μm image of Polaris and controlled the area filling factor by varying the length of the filaments. For each realization, we then calculated the  of the residuals between the best power-law fit and the net output power spectrum, as described in Sect. 3.

of the residuals between the best power-law fit and the net output power spectrum, as described in Sect. 3.

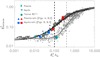

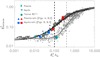

Figure 11 summarizes the dependence of  on ⟨δc⟩2 and Afil for Gaussian synthetic filaments. The map of the

on ⟨δc⟩2 and Afil for Gaussian synthetic filaments. The map of the  as a function of ⟨δc⟩2 and Afil is qualitatively similar for Plummer-like synthetic filaments. Figure 12 shows that there is a tight correlation between

as a function of ⟨δc⟩2 and Afil is qualitatively similar for Plummer-like synthetic filaments. Figure 12 shows that there is a tight correlation between  and ⟨δc⟩2 × Afil for both Gaussian (black solid circles) and Plummer-like filaments (gray solid squares), as expected from Eq. (12). In both cases,

and ⟨δc⟩2 × Afil for both Gaussian (black solid circles) and Plummer-like filaments (gray solid squares), as expected from Eq. (12). In both cases,  appears to be a non-linear function of

appears to be a non-linear function of  Afil, with a flat portion at low

Afil, with a flat portion at low  Afil values (i.e.,

Afil values (i.e.,  Afil ≲ 0.02 for Gaussian filaments,

Afil ≲ 0.02 for Gaussian filaments,  Afil ≲ 0.07 for Plummer-like filaments), a rising portion at higher

Afil ≲ 0.07 for Plummer-like filaments), a rising portion at higher  Afil values, with an inflection point close to

Afil values, with an inflection point close to  Afil ∼ 0.1 in the Gaussian case and

Afil ∼ 0.1 in the Gaussian case and  Afil ∼ 0.4 in the Plummer case (see Fig. 12). It can also be seen that, for the same value of

Afil ∼ 0.4 in the Plummer case (see Fig. 12). It can also be seen that, for the same value of  Afil, the

Afil, the  is lower for Plummer synthetic filaments than for Gaussian synthetic filaments9.

is lower for Plummer synthetic filaments than for Gaussian synthetic filaments9.

|

Fig. 11. Map of the χ2− variance of the residuals between the best power-law fit and the output power spectrum as a function of column density contrast (δc) and area filling factor (Afil) in a grid of simulations based on a set of 20 × 20 populations of Gaussian synthetic filaments, all 0.1 pc in width (see text of Sect. 7 for details). The white solid curve marks the fiducial limit |

Qualitatively, this behavior may be understood as follows. At low  Afil ≲ 0.02 values (or

Afil ≲ 0.02 values (or  Afil ≲ 0.07 for Plummer-like filaments), the contribution of synthetic filaments to the total power spectrum is negligible, and

Afil ≲ 0.07 for Plummer-like filaments), the contribution of synthetic filaments to the total power spectrum is negligible, and  is dominated solely by the residuals of the original background image. Therefore,

is dominated solely by the residuals of the original background image. Therefore,  retains the value

retains the value  it has for the original image and remains constant despite the addition of synthetic filaments. As

it has for the original image and remains constant despite the addition of synthetic filaments. As  Afil increases, the

Afil increases, the  for both Gaussian and Plummer filaments also increases, reaching a value of about

for both Gaussian and Plummer filaments also increases, reaching a value of about  at

at  Afil ∼ 0.1 (Gaussian case) or 0.4 (Plummer case). We take these values of

Afil ∼ 0.1 (Gaussian case) or 0.4 (Plummer case). We take these values of  Afil as fiducial limits for the detection of a characteristic filament width in the image power spectrum for Gaussian- and Plummer-shaped filaments, respectively. These fiducial detection limits are marked by black and gray vertical dashed lines in Fig. 12.

Afil as fiducial limits for the detection of a characteristic filament width in the image power spectrum for Gaussian- and Plummer-shaped filaments, respectively. These fiducial detection limits are marked by black and gray vertical dashed lines in Fig. 12.

|

Fig. 12.

|

To put the simulation results shown in Figs. 11 and 12 in context, we recall that the Polaris simulation of Fig. 5a in Sect. 3 had  Afil ∼ 0.018 and

Afil ∼ 0.018 and  of 0.034 (see Fig. 4c), which is nearly the same as the observed

of 0.034 (see Fig. 4c), which is nearly the same as the observed  (see Fig. 3). This particular simulation is marked by a blue triangle in the

(see Fig. 3). This particular simulation is marked by a blue triangle in the  plot of Fig. 12. The more extreme Polaris simulation presented in Fig. B.2a, for which there is a marginal detection of a characteristic scale in the residuals plot (see Fig. B.2c), has

plot of Fig. 12. The more extreme Polaris simulation presented in Fig. B.2a, for which there is a marginal detection of a characteristic scale in the residuals plot (see Fig. B.2c), has  Afil ∼ 0.087 and

Afil ∼ 0.087 and  (see red triangle in Fig. 12). Likewise, the blue and red square symbols in the

(see red triangle in Fig. 12). Likewise, the blue and red square symbols in the  plot of Fig. 12 mark the positions of the two sets of Aquila simulations presented in Figs. 8 and B.3, respectively.

plot of Fig. 12 mark the positions of the two sets of Aquila simulations presented in Figs. 8 and B.3, respectively.

The red square in Fig. 12 has  Afil ∼ 0.27 (and χvariance ∼ 0.28), significantly above the fiducial detection limit of 0.1, indicating that the signature of a characteristic filament width should be detectable in the power spectrum. This is indeed confirmed by visual inspection of Fig. B.3b and c. Most importantly, for both Polaris and Aquila, the real Herschel data lie in a portion of the

Afil ∼ 0.27 (and χvariance ∼ 0.28), significantly above the fiducial detection limit of 0.1, indicating that the signature of a characteristic filament width should be detectable in the power spectrum. This is indeed confirmed by visual inspection of Fig. B.3b and c. Most importantly, for both Polaris and Aquila, the real Herschel data lie in a portion of the  diagram where the filament contribution has a negligible impact on the power spectrum (see cross and plus symbols in Figs. 11 and 12). Also shown as a green filled circle in Fig. 12 is the locus of the Herschel data for the prominent filament system B211/B213 in Taurus (see Sect. 6), which has a very well characterized Plummer-like density profile with a power-law wing index p = 2 ± 0.2 (Palmeirim et al. 2013). It can be seen that the position of the Taurus B211/B213 data in Fig. 12 is in excellent agreement with our set of simulations for Plummer-shaped filaments with p = 2. Although the

diagram where the filament contribution has a negligible impact on the power spectrum (see cross and plus symbols in Figs. 11 and 12). Also shown as a green filled circle in Fig. 12 is the locus of the Herschel data for the prominent filament system B211/B213 in Taurus (see Sect. 6), which has a very well characterized Plummer-like density profile with a power-law wing index p = 2 ± 0.2 (Palmeirim et al. 2013). It can be seen that the position of the Taurus B211/B213 data in Fig. 12 is in excellent agreement with our set of simulations for Plummer-shaped filaments with p = 2. Although the  Afil ∼ 0.125 value of the Taurus B211/B213 data is greater than the fiducial threshold for Gaussian filaments, it remains much lower than the fiducial detection limit for Plummer (p = 2) filaments.

Afil ∼ 0.125 value of the Taurus B211/B213 data is greater than the fiducial threshold for Gaussian filaments, it remains much lower than the fiducial detection limit for Plummer (p = 2) filaments.

We conclude that the essentially scale-free power spectrum of the Herschel images observed toward molecular clouds such as Polaris, Aquila, or Taurus does not invalidate the existence of a characteristic filament width.

8. Summary and conclusions

We used numerical experiments to investigate the conditions under which the presence of a characteristic filament width can manifest itself in the power spectrum of cloud images. Our main findings and conclusions may be summarized as follows:

-

The detectability of a characteristic filament scale in the power spectrum of an ISM dust continuum image primarily depends on the parameter

Afil, where δc is the weighted average column density contrast of the filamentary structures and Afil their area filling factor in the image. A value

Afil, where δc is the weighted average column density contrast of the filamentary structures and Afil their area filling factor in the image. A value  Afil ⪆ 0.1 is required for the presence of a characteristic filament width to produce a significant signature in the power spectrum.

Afil ⪆ 0.1 is required for the presence of a characteristic filament width to produce a significant signature in the power spectrum. -

The Herschel Gould Belt survey images of nearby clouds typically have

Afil ≪ 0.1 and therefore lie in a region of the parameter space where filaments have a negligible impact on the power spectrum. Therefore, despite recent claims, the scale-free nature of the observed power spectra remains consistent with the presence of a characteristic filament width ∼0.1 pc.

Afil ≪ 0.1 and therefore lie in a region of the parameter space where filaments have a negligible impact on the power spectrum. Therefore, despite recent claims, the scale-free nature of the observed power spectra remains consistent with the presence of a characteristic filament width ∼0.1 pc. -

When the average filament contrast is low and/or when the filaments occupy a small area filling factor, the power spectrum is dominated by the fluctuations of the diffuse, non-filamentary component of the ISM.

-

Although a few filaments in the Polaris cloud have column density contrasts up to δc ∼ 0.9, their area filling factor is extremely low Afil ∼ 2%, resulting in a combined parameter

Afil ∼ 0.01 for Polaris. The overall power spectrum of the Herschel images of Polaris is scale-free because the filaments are not contributing enough power to produce a significant signature at the spatial frequency corresponding to the characteristic filament width of ∼0.1 pc.

Afil ∼ 0.01 for Polaris. The overall power spectrum of the Herschel images of Polaris is scale-free because the filaments are not contributing enough power to produce a significant signature at the spatial frequency corresponding to the characteristic filament width of ∼0.1 pc. -

Despite the presence of several supercritical filaments of ∼0.1 pc inner width in the Aquila cloud, the power spectrum of the Aquila Herschel images is also essentially scale free. Due to the larger distance of the Aquila cloud compared to Polaris, ∼0.1 pc filaments in Aquila subtend a smaller angular width scale on the sky, and therefore have a relatively low area filling factor. Overall, our simulations suggest that the observed population of Aquila filaments contributes only ∼1/5 of the total amplitude of the power spectrum of the Herschel 250 μm image.

-

Supercritical filaments with Plummer-like profiles and high column density contrasts lead to relatively small departures from a power-law power spectrum because the high contrast of the flat inner plateau in the density profile is compensated by broad power-law wings at large radii. The B211/B213 filament system in Taurus, for example, despite having a very high central column density contrast, remains largely undetected in the image power spectrum because of its Plummer-like density profile with p ≈ 2.

-

We conclude that the scale-free appearance of the power spectra of cloud images does not invalidate the finding, based on detailed Herschel studies of the column density profiles, that nearby molecular filaments have a common inner width ∼0.1 pc (Arzoumanian et al. 2011, 2019).

Note that Pfil(k) in Fig. 2 is almost flat at k < kfil and drops rapidly at k > kfil.

In order to capture the maximum rectangular area within the Polaris image for easier computation of the power spectrum, we rotated the original map in equatorial coordinate by 13.6° clockwise about its center and extracted the largest area excluding turn-around data points near the edges of the field.

The distance of the Aquila cloud is uncertain, with values ranging from 260 pc to 414 pc in the literature. Assuming the upper distance value would push kfil toward higher angular frequencies in Fig. 6b and c, making the detection of the 0.1 pc scale even more difficult in the power spectrum.

The column density contrasts of cold molecular filaments are somewhat higher than their surface brightness contrasts at 250 μm. To be on the conservative side, we used the observed distribution of column density contrasts for constructing synthetic filaments in the 250 μm images. The actual surface brightness contrasts are actually lower than what we assumed here.

A Plummer-like filament with p ≲ 2.6 contributes less power to the power spectrum at low angular frequency than a Gaussian filament with similar inner width and contrast (see Fig. 2b). Therefore, at k < kfil, Plummer-like filaments with p ≲ 2.6 lead to a lower overall  compared to Gaussian filaments.

compared to Gaussian filaments.

Acknowledgments

This work has received support from the European Research Council under the European Union’s Seventh Framework Programme (ERC Advanced Grant Agreement no. 291294 – “ORISTARS”). We also acknowledge financial support from the French national programs of CNRS/INSU on stellar and ISM physics (PNPS and PCMI). A.R, and N.S., acknowledge support by the French ANR and the German DFG through the project “GENESIS” (ANR-16-CE92-0035-01/DFG1591/2-1). P.P. acknowledges support from the Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia of Portugal (FCT) through national funds (UID/FIS/04434/2013), from FEDER through COMPETE2020 (POCI-01-0145-FEDER-007672), and from the fellowship SFRH/BPD/110176/2015 funded by FCT (Portugal) and POPH/FSE (EC). We are grateful to our colleague Alexander Men’shchikov for assistance with the getfilaments algorithm. This research has made use of data from the Herschel Gould Belt survey (HGBS) project (http://gouldbelt-herschel.cea.fr). The HGBS is a Herschel Key Programme jointly carried out by SPIRE Specialist Astronomy Group 3 (SAG 3), scientists of several institutes in the PACS Consortium (CEA Saclay, INAF-IFSI Rome and INAF-Arcetri, KU Leuven, MPIA Heidelberg), and scientists of the Herschel Science Center (HSC).

References

- André, P., Men’shchikov, A., Bontemps, S., et al. 2010, A&A, 518, L102 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- André, P., Di Francesco, J., Ward-Thompson, D., et al. 2014, Protostars and Planets VI, 27 [Google Scholar]

- Arzoumanian, D., André, P., Didelon, P., et al. 2011, A&A, 529, L6 [Google Scholar]

- Arzoumanian, D., André, P., Könyves, V., et al. 2019, A&A, 621, A42 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Auddy, S., Basu, S., & Kudoh, T. 2016, ApJ, 831, 46 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Falgarone, E., Panis, J.-F., Heithausen, A., et al. 1998, A&A, 331, 669 [NASA ADS] [Google Scholar]

- Federrath, C. 2016, MNRAS, 457, 375 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Fischera, J., & Martin, P. G. 2012, A&A, 542, A77 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Gao, Y., & Solomon, P. M. 2004, ApJ, 606, 271 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Heiderman, A., Evans, II., N. J., Allen, L. E., Huard, T., & Heyer, M. 2010, ApJ, 723, 1019 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Hennebelle, P., & André, P. 2013, A&A, 560, A68 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Inutsuka, S., & Miyama, S. M. 1997, ApJ, 480, 681 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Koch, E. W., & Rosolowsky, E. W. 2015, MNRAS, 452, 3435 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Könyves, V., André, P., Men’shchikov, A., et al. 2015, A&A, 584, A91 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Lada, C. J., Lombardi, M., & Alves, J. F. 2010, ApJ, 724, 687 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Marsh, K. A., Kirk, J. M., André, P., et al. 2016, MNRAS, 459, 342 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Martin, P. G., Miville-Deschênes, M.-A., Roy, A., et al. 2010, A&A, 518, L105 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Men’shchikov, A. 2013, A&A, 560, A63 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Miville-Deschênes, M.-A., Levrier, F., & Falgarone, E. 2003, ApJ, 593, 831 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Miville-Deschênes, M.-A., Martin, P. G., Abergel, A., et al. 2010, A&A, 518, L104 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Palmeirim, P., André, P., Kirk, J., et al. 2013, A&A, 550, A38 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Panopoulou, G. V., Psaradaki, I., Skalidis, R., Tassis, K., & Andrews, J. J. 2017, MNRAS, 466, 2529 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Roy, A., André, P., Arzoumanian, D., et al. 2015, A&A, 584, A111 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider, N., André, P., Könyves, V., et al. 2013, ApJ, 766, L17 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Shimajiri, Y., André, P., Braine, J., et al. 2017, A&A, 604, A74 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Tritsis, A., & Tassis, K. 2018, Science, 360, 635 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Ward-Thompson, D., Kirk, J. M., André, P., et al. 2010, A&A, 518, L92 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

Appendix A: Construction of synthetic filaments with Plummer-like density profiles

We adopted a slightly different technique to produce filaments with Plummer profiles compared to the convolution technique used to generate filaments with Gaussian profiles (see Sect. 2). A Plummer-like transverse profile was first constructed using the expression

where Rflat is the flat inner width and p is the logarithmic slope of the power-law wing at large radii (r > > Rflat). In order to suppress the strong edge effect at the two ends of the model filament, we tapered both edges with a Gaussian function. Figure A.1 shows an example of synthetic filament with a Plummer profile p = 2 and Rflat = 0.1 pc, similar to the Taurus B211 filament (Palmeirim et al. 2013). The power spectra of synthetic filaments with Plummer-like density profiles are discussed in Sect. 2.

|

Fig. A.1. Image of a synthetic filament with a Plummer-like transverse density profile with a flat inner radius, Rflat = 0.03 pc, and a power-law wing with index p = 2, projected at a distance of 140 pc. In this example, the level of filament contrast was adjusted to δc ∼ 10. |

Appendix B: Effect of extreme filament contrasts and area filling factors on the power spectrum

Figures B.2 and B.3 illustrate the consequences of adding populations of synthetic filaments with very high column density contrasts on the total power spectra of Polaris and Aquila, respectively. Figure B.2a displays the Herschel 250 μm image of the Polaris cloud populated with a set of high-contrast filaments with δc ∼ 1.1. The number of synthetic filaments was fixed to 100 and the distribution of synthetic filament lengths was adjusted so that the overall area filling factor was around Afil ∼ 7%. In this case, the synthetic filaments contribute a level of power (blue curve) almost equivalent to the power spectrum of the Polaris original image (cf. dashed green curve). This leads to an enhancement of power in the total power spectrum, which can be clearly seen in the residuals plot (red filled circles in Fig. B.2c). The χ2− variance of the residuals of the power-law fit in the angular frequency range of kmin < k < 1.5 kfil is about seven times larger than the χ2− variance metric for the Polaris original image.

|

Fig. B.1. Comparison of the Herschel/SPIRE 250 μm image of Polaris at the native beam resolution of 18.2″ (panel a –see Miville-Deschênes et al. 2010) with the filament-subtracted image of the same field, panel b obtained with the getfilaments algorithm (Men’shchikov 2013) and used as a “filament-free” background image in the numerical experiments shown in Figs. 5 and B.2. |

|

Fig. B.2. Same as Fig. 5 but for a population of synthetic filaments with higher column density contrasts δc ∼ 1.1, resulting in |

|

Fig. B.3. Same as Fig. 8 but for a population of synthetic filaments with a more extreme (and unrealistic) distribution of column density contrasts corresponding to ⟨δc⟩ ∼ 2.2 (see Fig. B.4) and an area filling factor Afil ∼ 5.5%, resulting in a combined parameter |

In the Aquila case, we created a population of 100 synthetic filaments rescaling the observed distribution of column density contrasts as shown in Fig. B.4. The maximum contrast sampled in the distribution was increased to  (compared to ∼3 in the original contrast distribution), and the peak of the distribution was shifted to

(compared to ∼3 in the original contrast distribution), and the peak of the distribution was shifted to  compared to 1 in the original distribution. The average contrast level of the synthetic filaments was about 2.2 and their area filling factor was as high as 5.5%. The resulting image obtained after adding this population of synthetic filaments to the Aquila original image is shown in Fig. B.3a. The power contribution due to the synthetic filaments, shown by the blue curve in Fig. B.3b, is significantly higher than the power spectrum amplitude of the Aquila original image (dashed green curve). Accordingly, the total power spectrum, [Pfil(k) + PAquila(k), solid black curve in Fig. B.3b] is amplified at angular frequencies k ≲ kfil. A strong deviation in the residuals plot (red symbols in Fig. B.3c) can also be seen.

compared to 1 in the original distribution. The average contrast level of the synthetic filaments was about 2.2 and their area filling factor was as high as 5.5%. The resulting image obtained after adding this population of synthetic filaments to the Aquila original image is shown in Fig. B.3a. The power contribution due to the synthetic filaments, shown by the blue curve in Fig. B.3b, is significantly higher than the power spectrum amplitude of the Aquila original image (dashed green curve). Accordingly, the total power spectrum, [Pfil(k) + PAquila(k), solid black curve in Fig. B.3b] is amplified at angular frequencies k ≲ kfil. A strong deviation in the residuals plot (red symbols in Fig. B.3c) can also be seen.

|

Fig. B.4. Two-segment power-law distribution of synthetic filaments contrasts adopted in the Aquila simulations of Appendix B. The distribution ranges from 0.3 to 15 and leads to a weighted average contrast of ∼2.2, significantly higher than in Fig. 7. |

Appendix C: Effect of filaments embedded in a scale-free synthetic background

We also generated a purely synthetic background image using the non-Gaussian fractional Brownian motion (fBm) technique of Miville-Deschênes et al. (2003), in such a way that the resulting power spectrum had a logarithmic slope γ = −2.7, mean brightness of the fluctuation ∼17 MJy/sr, and a standard deviation of 10 MJy/sr, similar to the statistics observed with Herschel in the Polaris field. On top of this scale-free image, a population of synthetic filaments with a lognormal distribution of (δc) contrasts (similar to that observed in Polaris) was added. The filaments had a Gaussian profile with an inner width of 0.1 pc projected at a distance of 140 pc, similar to the distance of the Polaris molecular cloud. They occupied an area-filling factor Afil ∼ 3% and had an average contrast δc ∼ 0.8. The resulting synthetic image after co-adding the fBm background image and the synthetic filaments is shown in Fig. C.1a. Inspection of the various components of the image power spectrum (shown in Fig. C.1b) shows that the contribution of the synthetic filaments to the global power spectrum is negligible and undetectable in this case as well.

|

Fig. C.1. Purely synthetic image, made up of a scale-free background image constructed using the fBm algorithm (panel a; cf. Miville-Deschênes et al. 2003). The embedded synthetic filaments have a lognormal column density contrast distribution in a range between 0.3 < δc < 2 and peak of δpeak ∼ 0.9. The overall area-filling factor of the filaments is Afil ∼ 3%. The filaments are of Gaussian profiles with a FWHM ∼0.1 pc at a distance of 140 pc (see text). Panel b: solid black curve shows the power spectrum of the scale-free background image and the synthetic filaments. The logarithmic slope of the power-spectrum is γ ∼ −2.7 ± 0.1. The dashed curve shows the power spectrum of the background image (γ ∼ −2.8). The blue solid line shows the power spectrum of the synthetic filaments. Panel c: residuals between the best power-law fit and the power spectrum data points (triangle symbols) of synthetic cirrus map. The |

All Figures

|

Fig. 1. Image of a simulated filament with a Gaussian transverse profile and a FWHM width of 0.1 pc, projected at a distance of 140 pc. Here, the level of filament contrast was adjusted so that δc ∼ 10. |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 2. Transverse profiles of several simple model filaments (a) and corresponding power spectra (b). Panel a: red curve shows the Gaussian column density profile of the filament displayed in Fig. 1, which has a FWHM width of 0.1 pc at a distance of 140 pc. The red vertical line marks the FWHM of the Gaussian profile. The black dashed and dotted curves display Plummer-like filament profiles with Rflat ∼ 0.03 pc and logarithmic slopes p = 1.5, 2, 2.6, and 4. Panel b: all power spectra were normalized to 1 at the lowest angular frequency |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 3. Panel a: Herschel/SPIRE 250 μm emission image of a part of the Polaris cloud. The HPBW angular resolution is 18 |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 4. Same as Fig. 3 but for a 250 μm image with an additional population of synthetic filaments. The population of synthetic filaments has a lognormal distribution of contrasts in the range 0.3 < δc < 2.0 with a broad peak around δpeak ∼ 0.9. The overall area filling factor of the synthetic filaments is Afil ∼ 3% and the |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 5. Same as Fig. 4 for synthetic filaments added to a filament-subtracted image of Polaris obtained with getfilaments (Men’shchikov 2013). The population of synthetic filaments is the same as that in Fig. 4. Panel b: green dashed line shows the best power-law fit to the power spectrum of the filament-subtracted background image of Polaris (with no synthetic filaments), which has a slope of γ = −2.4 ± 0.1. The solid black curve shows the total power spectrum of the filament-subtracted image plus synthetic filaments. The best-fit power-law (red curve) has a slope of γ = −2.5 ± 0.1, slightly steeper than the slope of the power spectrum of the filament-subtracted background image (dashed green curve). The blue curve is the power spectrum of the image containing only synthetic filaments. Panel c: black triangles are the same as in Fig. 3c and the red dots show the residuals between the best-fit power-law model and the power spectrum of the image including synthetic filaments. The |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 6. Panel a: Herschel/SPIRE 250 μm image of the Aquila cloud at the native resolution of 18 |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 7. Two-segment power-law approximation (black solid lines) to the distribution of filament column density contrasts observed in the Aquila molecular cloud (Arzoumanian et al. 2019): dN/dlog(δc)∼const for 0.3 ≤ δc ≤ 1, and d |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 8. Same as Fig. 6 but for a simulated image including a population of synthetic filaments with a realistic distribution of column density contrasts (see Fig. 7) added to a filament-subtracted image of the Aquila cloud. Panel a: simulated image. The weighted average contrast ⟨δc⟩ of the distribution of synthetic filaments is 0.96 and the total area covering factor Afil is 5.5%, leading to |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 9. Left panel: Herschel/SPIRE 250 μm image of the B211/B213 region in Taurus at the native beam resolution of 18.2″, but rotated in equatorial coordinates in clockwise direction by 37.4°. (see Palmeirim et al. 2013). Right panel: fully synthetic image mimicking the main features of the real image shown in the left panel, and resulting from the co-addition of a synthetic filament image and a synthetic background image. The synthetic filament image was based on the Plummer-like model of the B211 filament reported by Palmeirim et al. (2013): flat inner radius Rflat = 0.035 pc, contrast δc ∼ 6, and power-law index p = 2 at large radii. The background image was modeled as non-Gaussian cirrus fluctuations with a logarithmic power spectrum slope of −3 (see text for details), plus low-contrast filamentary structures resembling striations. The synthetic striations were placed such that their long axis is perpendicular to the main filament at a regular separation of 0.1 pc. |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 10. Comparison of the power spectrum of the Herschel/SPIRE 250 μm image of Fig. 9a (black solid curve) with that of the synthetic image of Fig. 9b (red curve). Note the absence of any significant feature around k ∼ kfil (vertical dashed line) in both power spectra. |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 11. Map of the χ2− variance of the residuals between the best power-law fit and the output power spectrum as a function of column density contrast (δc) and area filling factor (Afil) in a grid of simulations based on a set of 20 × 20 populations of Gaussian synthetic filaments, all 0.1 pc in width (see text of Sect. 7 for details). The white solid curve marks the fiducial limit |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 12.

|

| In the text | |

|

Fig. A.1. Image of a synthetic filament with a Plummer-like transverse density profile with a flat inner radius, Rflat = 0.03 pc, and a power-law wing with index p = 2, projected at a distance of 140 pc. In this example, the level of filament contrast was adjusted to δc ∼ 10. |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. B.1. Comparison of the Herschel/SPIRE 250 μm image of Polaris at the native beam resolution of 18.2″ (panel a –see Miville-Deschênes et al. 2010) with the filament-subtracted image of the same field, panel b obtained with the getfilaments algorithm (Men’shchikov 2013) and used as a “filament-free” background image in the numerical experiments shown in Figs. 5 and B.2. |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. B.2. Same as Fig. 5 but for a population of synthetic filaments with higher column density contrasts δc ∼ 1.1, resulting in |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. B.3. Same as Fig. 8 but for a population of synthetic filaments with a more extreme (and unrealistic) distribution of column density contrasts corresponding to ⟨δc⟩ ∼ 2.2 (see Fig. B.4) and an area filling factor Afil ∼ 5.5%, resulting in a combined parameter |

| In the text | |

|